Theories of the Work Life Balance | Reflection

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Project Management |

| ✅ Wordcount: 5110 words | ✅ Published: 11 Sep 2017 |

MY STORY

For many people, there is an aha moment, a point in time, often a trigger, that forces them to reassess where they are in life. They begin to question what toll long working hours are having on their life and where to next.

My story is a little different to this scenario; there was no aha moment. For me, what started soon after leaving high school, quickly became a great habit that has held me in great stead. And, I’m proud to say that I’ve continued to achieve balance between home and work life to this day.

As mentioned, my journey started in my late teen years, out of sheer necessity. I was working full time and commenced my university degree. Like many part-time students, I attended university three nights a week from 6 pm to 9 pm. In order to get through university and do the best I could (which because I was a high achiever I gave myself no choice but to do), I had to get to lectures (no online lectures or internet in those days, unfortunately) three nights a week. The other nights were dedicated to assignments, study, etc. That meant leaving work on time every night. But I wanted to be a high performer at work, too. I had the belief that I could do both and made choices accordingly.

Being young and naïve, I didn’t think about or probably even know the perceived culture that exists in many workplaces (and, on reflection, existed in the company I was at) that you needed to be seen in the office to climb the corporate ladder. All I knew was that I had lots of work to get done and only limited time to do it.

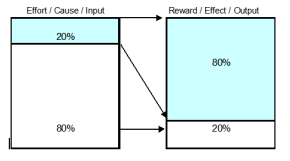

I soon became Miss Effectiveness, removing inefficiencies-removing so-called efficiencies that weren’t effective-and, in essence, making each day as productive as possible. Not that I knew it at the time, but I was practicing the principles of the 80/20 rule and Parkinson’s Law (expanded upon in subsequent chapters). I focused on the 20% of effort that provided 80% of the productive outcomes and restricted the time I had to get the work done, and it got done.

I used the same tools and techniques from my productivity toolkit when I changed jobs part way through my degree, and replicated the 9-to-5 achievement. I ticked the box of graduating from University after four years (with a few summer schools thrown in, to get through it in record time for a part timer). In addition, I had achieved at work, getting promoted to middle management by the time I was degree qualified.

With this recipe for achievement, why would I change my approach post graduating? Why would I revert to the all-so-familiar habits of others in the workforce of working long hours?

I continued to pack up and leave the office at 5 pm or 5.30 pm post my degree. If anyone in the office were to remark, I’d say I was doing post grad studies (which I was), or putting the finishing touches to the new house my husband and I had moved into (which I was). Externally, I occasionally needed to provide the reason why I left work on time, but internally, I knew no explanation was needed. I got through my work and more, and was living proof that you don’t do a good job if your job is all you do!

I was in my mid-twenties and thought I had this balance thing all worked out, when the greatest events of my life occurred-the birth of my beautiful boys (now men). Mitch was born first and then, two years later, Layton. And, for any parent, you know that a child will turn your whole life upside down-an incredibly positive upside down, but nevertheless upside down! Now, I not only needed to juggle work and interests outside of work, but the love, care and nurturing of two other human beings.

I was envious of the Mums or Dads who were content to take 12 months or more off work to care for their children. Unfortunately, I wasn’t so content and missed the stimulation of the work environment, but yep, you guessed it: I wanted to have my cake and eat it, too. I wanted to work, but I wanted to be there for my boys. And, I didn’t want to miss out on all those milestones-from newborn till today. I started working from home a lot, and worked out that, with focus, working from home can be as effective, and often more effective, than being present in the office.

When Mitch and Layton were three and one, we moved to a new home. We hadn’t planned ahead for the move, and hence, hadn’t planned ahead for childcare spots close to our new home (it wasn’t possible to commute to the previous childcare). Finding childcare was incredibly difficult, and it was before the days of nannies (other than for the very wealthy). Most centres didn’t have vacancies, and for those that did, there was a reason (not a good reason) they did!

We found a suitable child care centre, but with one catch: its hours were 8 am to 4 pm. The proximity to the childcare centre, relative to work, made sense for me to do the drop off and pick up. The child care centre was only about 20 minutes from work, but that would mean a maximum work day in the office of 8.20 am to 3.40 pm. It was at that point that both I, and the company I worked for, had a tough decision to make. I either worked 8.20 am to 3.40 pm in the office or I didn’t work at all.

I committed to the Company that the work would get done, and fortunately, they were willing to take the risk and see how things would go. From that day and for the next four years, I finished work at 3.40 pm each and every day with further hours of work from home each evening.

Two years into my 3.40 pm finish years, I was appointed Financial Controller of McDonald’s Australia. At that time, I was part of the senior leadership team and had a team of about 50 employees working within my team. Yes, there were absolutely days that it was tough, really tough, to race out the office door at 3.40 pm, and it took a lot of co-ordination and discipline, but I had no choice. If I wasn’t at child care at 4 pm to pick up my boys, there would be a financial penalty. But, the financial penalty was nothing in comparison to the “mum penalty,” the guilt of my children thinking Mummy wasn’t coming.

Not sure if to include photos – but would need to be cropped!

Not sure if to include photos – but would need to be cropped!

I’d be lying if I said there was no guilt leaving the office when my boss, my peers and my team were still working away. But guilt versus enjoying everything in life – you chose?

Post the preschool days, I was adamant I wanted to be there for all those important things in my children’s lives-whether that be reading groups, sports carnivals, musical performances, charity days or school community involvement. And I’m very proud to say, I’ve been there for most. There were days that I was torn between going to work and going to the school event. I recall someone saying: In years to come, you won’t remember having attended a particular work meeting or event, but you will always remember attending that special event in your child’s life. And, they will always remember you being there, too.

You may say I was fortunate to have the sort of job that provided flexibility; but, there were plenty around me, actually most around me, that could have made that choice themselves, but didn’t. I agree that in some jobs, it’s just not possible; but in most corporate roles (with lots of organisation[O1] and effectiveness), the choice is there. You know the saying ‘you make your own luck.’ I think this applies here, too. It’s up to you.

Fast forward 10 years or so – I’ve done a lot in the community whilst holding down demanding roles. Today, I no longer have the demands of part-time study or young children. My boys are now teenagers, but it is very rare to see me in the office past 5.30 pm. Today, the child care demands are replaced by a goal to run a half marathon, perhaps attend a school meeting, volunteer at an event, or simply to be home to have dinner with the family.

Sure, in all these years, I’ve done my fair share of work at night from the comfort of my home. But, it has allowed me to have it all-a career, sharing all those milestones with my family, good health, community involvement-having it all. And, I wouldn’t change it for the world.

The 80/20 Principle and Parkinson’s Law are two approaches to heighten productivity, with each being inversions of the other: The 80/20 Principle suggests limiting tasks to the important, so you can decrease work time and Parkinson’s Law proposes defining a shorter time span for working to ensure you do restrict tasks to important ones. The best outcomes can be achieved by using both together, whereby you identify the tasks that maximise output and define very short and clear deadlines in scheduling them.

The 80/20 Principle – more effectively using your time

Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian economist, discovered the 80/20 principle in 1897 when he observed that 80 percent of the land in England (and every country he subsequently studied) was owned by 20 percent of the population. Pareto’s theory of predictable imbalance has since been applied to almost every aspect of modern life.

Richard Koch took Pareto’s Principle and applied it to business, productivity, and life. The core of 80/20 thinking is that 20% of your effort yields 80% of your results. Conversely, you can use this idea to become aware of the 80% of your efforts that yield only 20% of your accomplishments, and trim the excess fat.

When you stop thinking of all activities as equal, and begin giving proportionately more time to the ones that impact your success, the results will be life changing.

IBM was one of the earliest corporations to use the 80/20 Principle. In 1963, IBM discovered that about 80% of a computer’s time was spent executing about 20% of the operating code. The company immediately rewrote its operating software to make the most used 20% very accessible and user friendly, thus making IBM computers more efficient and faster than competitors’ machines for the majority of applications.

There are loads of business examples of the 80/20 Principle. This includes realising that 80 percent of a company’s output is achieved by 20 percent of its employees, and 80 percent of a company’s revenues come from 20 percent of its customers. It won’t be exactly 80/20, but it is highly probable in business that a minority is creating a majority. It may be roughly 90/10, 70/30 or 60/40.

The 80/20 ratio applies to both your work day and your life outside work. You probably make most of your phone calls to, or spend most of your time with, a limited amount of the people you have numbers for and know. You probably wear 20% of your wardrobe 80% of the time. And, the majority of the times you eat out, you probably dine at the same 20% of the restaurants you know.

Results of a global six-year study with over 350,000 participants, showed there is roughly a 60/40 split (a variation of the 80/20) of time being spent on important and unimportant tasks. That is, most people spend about 40% of their time (that’s two working days) doing stuff that doesn’t matter. If you can reclaim even a little bit of that time, you can be amazingly more effective and productive, not to mention you can enhance the quality time you now have for family and friends.

The 80/20 principle suggests that there is a huge amount of waste everywhere and asserts that there is no shortage of time, given we only make effective use of 20% of our time. The 80/20 Principle says that if we doubled our time on the top 20% of activities, we could achieve 60% more in much less time

The 80/20 Principle: The Secret to Achieving More with Less by Richard Koch talks about the top 10 low-value uses of time:

- Things other people want you to do

- Things that have always been done this way

- Things you’re not usually good at doing

- Things you don’t enjoy doing

- Things that are always being interrupted

- Things few other people are interested in

- Things that have already taken twice as long as you originally expected

- Things where your collaborators are unreliable and low quality

- Things that have a predictable cycle

- Answering the telephone/responding to emails

The idea is that much related to the above 10 items makes up about 80 percent of your day, and only contributes to 20 percent of your results. You can only spend time on high-value activities, the 20 percent, if you no longer spend time on low-value uses of time. So, in order to boost your productivity, you must eliminate or substantially reduce the time you spend on the above.

Do you know what you spend your hours in the office doing? Studies and data have shown that how we think we spend our time has little to do with reality. You can gain more control over your time and your work by taking one small step right now. Challenge yourself to understand what you spend 80% of your time on. Simply begin to look for the signs that will tell you whether you’re in your 20 percent or your 80 percent. You may want to document what you do, hour by hour, for a few weeks (perhaps you could combine this with the daily activity log suggested in the chapter on Managing your Energy) to obtain clarity on your 80/20.

There is no more effective way to reduce the time taken to complete a task in your 80 percent than not doing it at all. Too often, productivity, time management, and optimisation[O2] means we avoid the real question of whether we actually need to be doing the task at all. It’s often much easier to remain busy, to work a little later on a given night than step out of your comfort zone of eliminating a task. Often, you’ll have grown comfortable with doing a task, regardless of whether it’s the best use of your time. As Tim Ferriss, self-help author and speaker says, “Being busy is a form of laziness-lazy thinking and indiscriminate action.”

There is not enough time to do all the nothing we want to do (Bill Watterson).

Deciding what not to do is as important as deciding what to do.” (Steve Jobs)

Be strong and make decisions to delete any task not leading you toward your values and your goals. A “stop doing” list is as important as a “to-do” list.

By understanding what to stop doing, you can focus on the high-value items that should take up the most productive 20 percent of your time, which are, according to Richard Koch:

- Things that advance your overall purpose in life

- Things you have always wanted to do

- Things already in the 20/80 relationship of time to results

- Innovative ways of doing things that promise to slash the time required and/or multiply the quality of results

- Things other people tell you can’t be done

- Things other people have done successfully in a different arena

- Things that use your own creativity

- Things that you can get other people to do for you with relatively little effort on your part

- Anything with high-quality collaborators who have already transcended the 80/20 rule of time, who use time eccentrically and effectively

- Things for which it is now or never

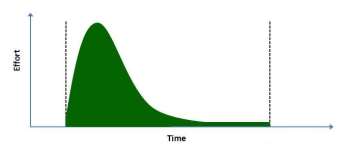

Parkinson’s Law – work expands to fill the time available for it

Parkinson’s Law is the adage that “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion,” which means that if something is due next week, you will likely use the time allotted and the work will only be finished next week. If you’re given two months for the same work, then the work will take two months to complete. You will mentally be “pacing” yourself based on the time you have, so even if you want to work faster, it will be mentally challenging.

Cyril Parkinson, a British historian, first observed the trend during his time with the British Civil Service. He noted that as bureaucracies expanded, they became more inefficient. He then applied this observation to a variety of other circumstances, realising that as the size of something increased, its efficiency dropped. He found that even a series of simple tasks increased in complexity to fill up the time allotted to the outcome. As the length of time allocated to a task became shorter, the task became simpler and easier to solve.

Well-known terms are the outcome of Parkinson’s Law:

- If you wait until the last minute, it only takes a minute to do.

- Work contracts to fit in the time we give it.

- The amount of time that one has to perform a task is the amount of time it will take to complete the task.

- The demand upon a resource tends to expand to match the supply of the resource.

If you truly focused intently, how long do you think it would take you to finish a day’s worth of work? Do you think you could be done in 6 hours instead of 8? Maybe 4? The problem is that if you have to stay until 5 pm, there really isn’t a way for you to find out.

Per Timothy Ferriss in his book, The 4-Hour Work Week: “The world has agreed to shuffle papers between 9 am and 5 pm., and since you’re trapped in the office for that period of servitude, you are compelled to create activities to fill that time. Time is wasted because there is so much time available. Since we have 8 hours to fill, we fill 8 hours. If we had 15, we would fill 15; however, if we had an emergency and needed to suddenly leave work in 2 hours, but had pending deadlines, we would miraculously complete those assignments in 2 hours.”

You are forced to complete tasks in a given time, if you are experiencing time pressure. When there is no pressure attached to a task, it will take longer to complete. In fact, the longer you have to complete the task, the longer it will take you. And, your perception of the importance of a task is influenced by the time allocated. A task that needs completion within a day isn’t perceived as important, but a task that’s to be finished in two months will be. Perceptions of complexity are also related to the allocated time; the more time allocated, your perception will likely be that better quality work is required. Also, the more work your mind thinks it will take will cause you to perceive the task as overly complex and difficult. Waste thrives on complexity; effectiveness requires simplicity.

Parkinson’s Law is the reason you may hear people say, “If you want something done, ask a busy person,” even though this idea is somewhat paradoxical.

“The more things you do, the more you can

get done.” (Lucille Ball)

My early working years, and then the years to follow with young children, were spent practicing Parkinson’s Law at its best. I gave myself very short deadlines due to my time constraints, and I also imposed short deadlines on those around me to coincide with my time frames. The result was that everything got done and more, in a very short time frame. If I had more time to get the work done, I don’t necessarily think more would have been done.

Today, when I create self-imposed deadlines, the relevant activity/task gets done in a very short time frame. It becomes a game, a competition against the clock that I must win and I do!

Use Parkinson’s Law to Your Advantage:

- Embrace deadlines and constraints! Force yourself to work against the clock.

- When you are given a task without a deadline, set the deadline yourself. I often set a deadline that I need to finish a task by 10 am, another task by 11 am, and a third task by 12 noon. I even use this principle at home; for example, I need to complete the ironing in a certain time. Without doubt, I complete the task (in this example, the ironing) in a shorter period of time with no risk to the quality of the finished product. You will be surprised how a deadline motivates you into action, and amazed how productive you can become.

- Always state a deadline when you delegate a task to someone else. The shorter the deadline, the better.

- Deadlines should be as immediate as possible and time constraints as short as workable. The more time pressure you feel, the more focused you will be and the more work you can complete.

- Blackmail yourself: Get an accountability partner who will force you to pay up if you don’t meet your deadline.

Cut your work hours in half when you sit down to plot out your day. It’ll force you to be extremely picky when it comes to the tasks you agree to take on or contribute to, and it’ll give you time to make sure these high priorities actually get done on time.

The overarching lesson from Parkinson’s Law is that restrictions can actually create freedom. How can you add artificial parameters to your life and work, in order to become more productive and more prolific and to operate on a bigger scale?

Check point:

- Do you know what your 80/20 is? What tasks are you spending most of your time on that are only delivering you very little benefit – both at home and at work? Would documenting your day help you understand your 80/20?

- What needs to go on your “stop doing” task list?

- What changes are you going to make today to give you more time and increase your output?

- Experiment with setting tough deadlines and note the difference and enforce the same of others.

- Use the spare hours from getting the job done quicker to get out of the office and have fun!

Unless you intentionally schedule time for certain work, you tend not to get to it. In order to improve this situation, each night, make it a habit to identify the most important challenge for the next day. Make this challenge your very first priority the next morning.

“If it’s your job to eat a frog, it’s best to do it first

thing in the morning. And If it’s your job to eat

two frogs, it’s best to eat the biggest one first.”

(Mark Twain)

Your “frog” is the task that will have the greatest positive impact on your outcomes at the moment. If you have two frogs, i.e. two tasks, then start with the biggest, hardest, and most important task first.

Your frog is your “Most Important Task” (MIT). You only have limited time and energy, so it’s crucial you focus on completing the most important tasks that will make the biggest impact first. Do this before you spend your time and energy on anything else.

The idea is that no matter what else is going on in the day, the MITs are what you want to be sure of doing. Usually the small, unimportant tasks that need to get done every day get in the way of important tasks. However, if you make your MITs your first priority each day, the important stuff will get done instead of the unimportant.

Most of us are at our cognitive best, our brain at optimal performance, about two to four hours after we’ve woken up. Yet, we often waste that time on easy, relatively unimportant tasks that could be postponed to later in the day like emails, or our commute or that morning coffee run.

However, if you aren’t at your cognitive best in the morning, shift the big task (the MIT) to the time when your mental powers are at their height.

Combining this technique with Parkinson’s Law, by setting an artificial deadline, is enormously effective. If you set a goal to finish all of your MITs by X time, you’ll be surprised how quickly you can complete the day’s MITs.

How to find your 3 most important tasks:

- Write down everything on your to-do list, both business as usual and project-related tasks.

- Ask yourself: If I could only do one thing all day (and you want it to be the task that will have the greatest effect on your business), what task would I chose?

- Move that task to your MIT list.

- Replicate this for a second and, if needed, third MIT.

The tasks on your MIT list will stand for at least 80% of your output. Focus on the MITs and try to find ways to either eliminate or decrease the amount of time you spend on other tasks.

The MIT prioritisation process can be utilised beyond the work environment; it becomes useful in managing your home priorities, too.

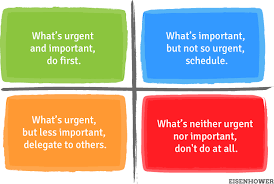

THE EISENHOWER URGENT/IMPORTANT PRINCIPLE

Dwight D. Eisenhower, the 34th President of the United States, developed the urgent/important principle or matrix. The Eisenhower Matrix is a method of determining your MITs and prioritising other things on your to-do list.

Eisenhower’s strategy for getting organized and taking action is based on separating your actions by looking at four possibilities defined by four quadrants:

Q1Urgent and important (tasks you will do immediately)

Q2Important but not urgent (tasks you will schedule to do later)

Q3Urgent but not important (tasks you will delegate to someone else)

Q4Neither urgent nor important (tasks that you will eliminate)

According to Eisenhower, what is important is seldom urgent and what is urgent is seldom important.

Urgent tasks are things that you feel like you need to react to: emails, phone calls, texts. Important tasks are things that contribute to our long-term mission, values, and goals.

We should seek to spend most of our time on Q2 activities (important but not urgent), as they’re the ones that provide us fulfillment and success. However, there are a number of key challenges to spending enough time and putting energy into Q2 tasks:

- Knowing what is truly important to you. If you don’t know what specific values and goals matter most to you, you can’t determine those tasks you should be focusing your time on for reaching those aims.

- Present bias. We each have a tendency to focus on whatever is perceived as the most urgent at the moment-our default mode. Motivation is a challenge when there is no looming deadline. Departing from this default position requires a good measure of willpower and self-discipline. As noted in the previous chapter on Parkinson’s Law: where there is no deadline, be sure to set your own short deadline.

Given Q2 activities aren’t pressing for our immediate attention, they typically keep getting put to the bottom of the pile, as we tell ourselves, “I’ll get to those things ‘someday’ after I’ve taken care of the urgent things.” But “someday” will never come, if you’re waiting to do the important things until your schedule clears up a little. You’ll always find things to do that make you too busy. In order to focus on Q2, then you need to find time-to consciously decide that you are going to make time and there will be no buts.

Quadrant 3: Urgent and Not Important Tasks

Quadrant 3 tasks are activities requiring our attention now (urgent), but don’t actually help us achieve our goals or fulfill our mission (not important). Most Q3 tasks are requests from other people, helping them reach their own goals and meet their priorities.

Examples of Quadrant 3 activities include most emails, phone calls, text messages or colleagues coming to your desk during your golden hour to ask a favour.

According to Stephen Covey (author of 7 Habits of Highly Effective People), many people spend most of their time on Q3 tasks, thinking they’re working in Q1. People feel important as Q3 tasks do help others out. They are also usually tangible tasks, which gives you that sense of satisfaction as you complete them. It feels empowering to check something off your list.

While Q3 tasks help others, they don’t necessarily help you. They need to be balanced with your Q2 activities. Otherwise, you’ll end up feeling like you’re accomplishing a lot from day-to-day, but eventually, you’ll realise that you’re failing to make any progress when it come to your own long-term goals.

Quadrant 4: Not Urgent and Not Important Tasks

Quadrant 4 activities aren’t urgent and aren’t important. They are primarily distractions. They include scrolling through social media, mindlessly surfing the web or watching TV. Aim to spend no more than 5% of your time in this quadrant.

By investing time in Q2’s activities, you can eliminate much of the issues of Q1, balance the requests of Q3 with your own needs, and enjoy the time-out of Q4, feeling that you’ve earned Q4. By making Q2 tasks your top priority, regardless of the emergency, or deadline you’re facing, you’ll have the mental, emotional, and physical strength to respond positively, rather than react defensively.

DON’T PRIORITISE THE WEEK WHILE YOU’RE IN IT – A PERFECT FRIDAY TASK

Lots of offices have staff meetings on Monday mornings to priortise and plan the week; but, prioritising the week, or even just the Monday while you’re in it, isn’t nearly as effective as doing it ahead of time. Friday is a perfect day to talk about the coming week. You can reflect on what you accomplished over the previous week, what you want to accomplish in the next week, and you can think about what strategies you’ll use to achieve that.

In addition to holding staff meetings to prioritise the week ahead, you can denote Fridays as a perfect day for individual planning and prioritisation. Ring fence an hour appointment with yourself for figuring out how to progress, track, research, strategise, or conduct any of those “thinking tasks” that normally take a back seat.

Like most, I was a Monday morning team catchup person, but now, I have made the sw

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal