Impact of the World War 2 Utility Scheme on British Fashion

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Fashion |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3154 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

Back to Basics: The WW2 Utility Scheme and its Impact on British Clothing, Body Image, and Society.

Synopsis

This article will look into the Utility Scheme put in place in the Second World War and the impact it had on fashion, in particular, women’s fashion. I will break down the meaning of the Utility Scheme with its intentions for salvaging materials, along with the impact this had on the clothes and social changes the scheme inspired, all whilst investigating the definitions of fashion. This article’s main inspiration has come from Peter McNeil’s article entitled ‘Put Your Best Face Forward’: The Impact of the Second World War on British Dress.

I will argue the importance of the roles: Form and Function, gender in clothing with relation to femininity and masculinity, and social class signifiers when considering their influences and relevance in today’s society. I will give supporting credibility and evidence to my arguments with reference to other peer-reviewed Journal Articles as well as the application of my own knowledge.

I will also look at all this in relation to the concept of the Body of the Ideal Woman, after all, ‘fashion’ does not just mean clothing, but body images also. It is imperative to understand the importance of artists, designers and techniques in reference to fashion, Modernism and Post-Modernism along the way so I will include a list of keywords and key names for assistance in understanding.

Keywords and Key-names

A list of useful words and names for possible further research:

- Utility/Utilitarian, Modernism, Post-Modernism, Rationing, Austerity, Recycling, Coupons, Functionality, Resourcefulness

- Hardy Amies, Norman Hartnell, Edward Molyneux, Digby Morton, Victor Stiebel, Bianca Mosca, Christian Dior.

Understanding Circumstance

It is perhaps a suitable place to start this journal with a bit of context. The Second World War started 1st September 1939 and lasted until 2nd September 1945, spanning over 6 years. During which time it was obvious that rationing for civilians was an absolute necessity.

Here we see a list of foods rationed:

- Bacon & Ham 4 oz

- Other meat value of 1 shilling and 2 pence (equivalent to 2 chops)

- Butter 2 oz

- Cheese 2 oz

- Margarine 4 oz

- Cooking fat 4 oz

- Milk 3 pints

- Sugar 8 oz

- Tea 2 oz

- Eggs 1 fresh egg (plus an allowance of dried egg)

(Wilson, S 2018)

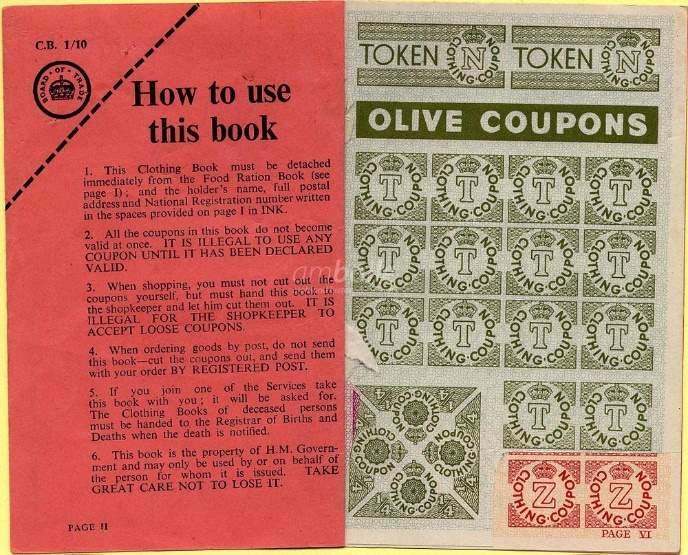

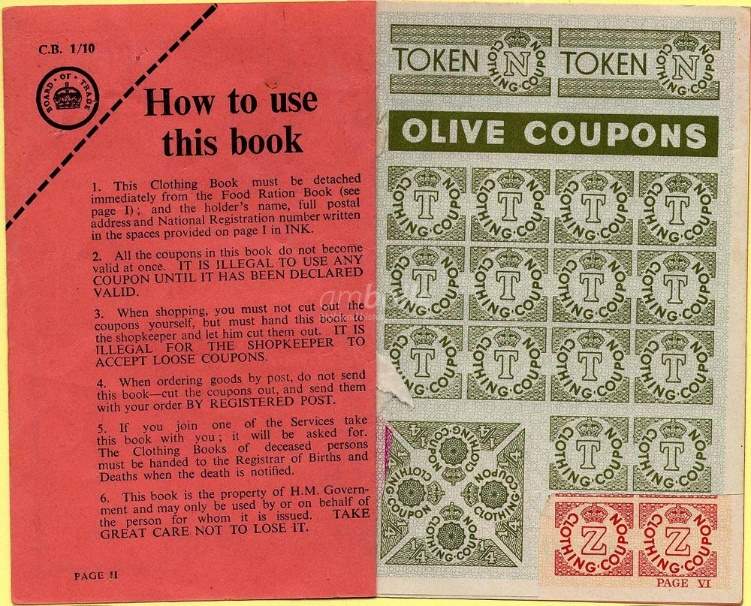

Because of the sheer lack of resources, clothing and materials were limited also. There was a points system put in place as well as tokens or coupons and log books. Each person gets 24 coupons, which have had to last for varying periods (W. Hill, 2005), by 1945 this had been further reduced to just 41 coupons per year (N. Rothstein, 1984).

(Fig. 1)

Here is a table I have made showing the number of points it costs for men and women for individual items according to an article in the BBC archives of WW2 memories, Rationing and Shortages by Ralph W. Hill:

|

Women |

Men |

|

Big Coat 18 |

Suit 26 |

|

Shoes 7 |

Overcoat 16 |

|

Vest 3 |

Mackintosh 16 |

|

Knickers 3 |

Jacket 13 |

|

Petticoat 3 |

Trousers 8 |

|

Corsets 3 |

Shoes 9 |

|

Slippers 5 |

Slippers 7 |

|

Dress 7 |

Singlet 3 |

|

Gloves 2 |

Shirt 5 |

|

Scarf 1 |

Collar 1 |

|

Pyjamas 8 |

Pyjamas 8 |

|

Stockings 2 |

Tie 1 |

|

1 Pair of Socks 1 |

1 Pair of Socks 1 |

(W. Hill, 2005.)

W. Hill explains that these facts and figures came from notes made by his father for his relatives to be informed.

Fashions with rations

Taking all this into account, items were still expensive, including hats. According to Peter McNeil in his article Put Your Best Face Forward: The Impact of the Second World War on British Dress, the war was extremely costly in more ways than one. In 1941, clothing prices increased on average 175 per cent compared to pre-war, with usual shipping methods halted due to Germany’s attacks which were one of the reasons for rationing of clothes.

‘The number of buttons, seams, and pleats, and the amount of ruching and gauging [were] strictly limited; no braid, embroidery or lace is to be used.’ (McNeil, 1993).

Designers tackled the current situation and remedied solutions in the forms of square shoulder lines, shorter skirts and reduction of pleats, all-in-all less using less material. It is important to acknowledge menswear adaptations also:

‘New restrictions dictated the width of trouser bottoms, and banned trouser turn-ups, elastic in waistbands, and zip fasteners.’ (McNeil, 1993).

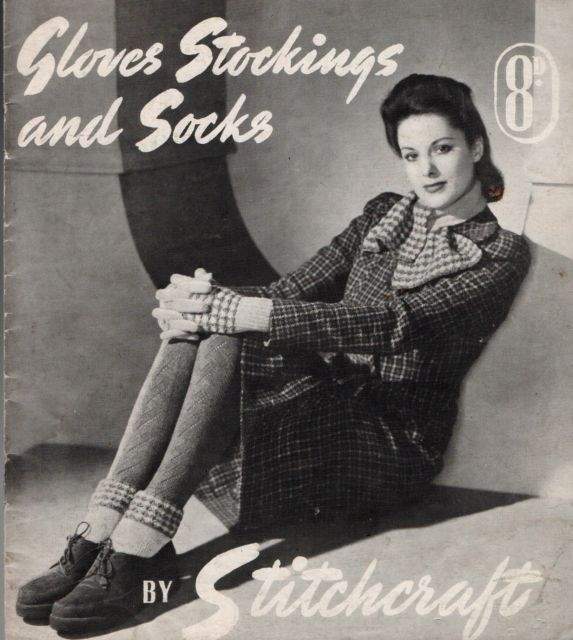

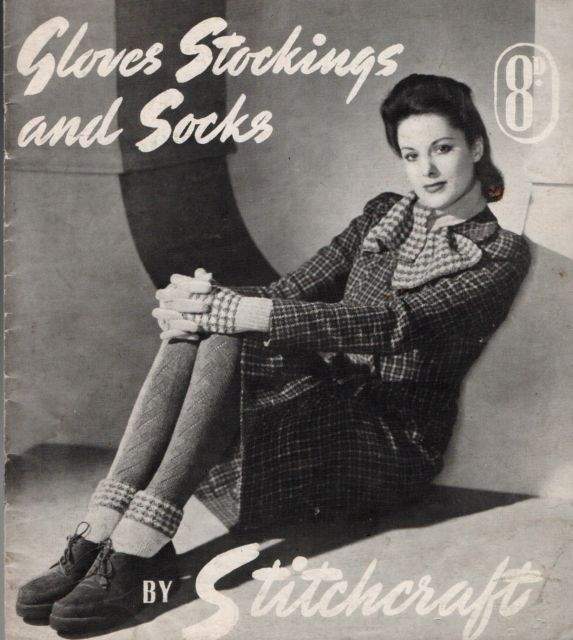

Razor blades, hair-cream, and matches were also very scarce. Interestingly, women were permitted to go to service without stockings or hats and for it to still be considered acceptable. This bought about alternatives for stockings and hats, knitted varieties became available for stockings and women’s hats were replaced by headscarves whereas men generally went hatless. Savvy substitutes were encouraged, wartime issues of Stitchcraft published guides on how to make your own stockings, hats gloves, socks and even shoes.

(Fig. 2)

Service women- Beauty in Duty

Resourceful, imaginative, altering and recycling were all needed to assist in austerity. Of course, these knitting guides were aimed towards civilian women who had leisure time. The service women’s uniform was seen as utilitarian, however, not as utilitarian as the men’s uniform. Men’s uniform was designed to exhibit power and presence, women’s uniform was designed to exhibit their maintenance of feminine elegance (McNeil, 1993) whilst getting their jobs done. Frequent scrutiny was put upon women, in relation to their hairstyles and makeup, to reiterate that servicewomen were not masculinized due to the war. This being said, shoulder pads, trousers, overalls and dungarees were absolutely needed for practicality and safety. The Irish designer Digby Morton (1906-83) designed the new uniforms for the Women’s Voluntary Services (Goodyear, 2003.) with all this in mind. The image below entitled Fig.3 shows examples of said uniforms.

Resourceful, imaginative, altering and recycling were all needed to assist in austerity. Of course, these knitting guides were aimed towards civilian women who had leisure time. The service women’s uniform was seen as utilitarian, however, not as utilitarian as the men’s uniform. Men’s uniform was designed to exhibit power and presence, women’s uniform was designed to exhibit their maintenance of feminine elegance (McNeil, 1993) whilst getting their jobs done. Frequent scrutiny was put upon women, in relation to their hairstyles and makeup, to reiterate that servicewomen were not masculinized due to the war. This being said, shoulder pads, trousers, overalls and dungarees were absolutely needed for practicality and safety. The Irish designer Digby Morton (1906-83) designed the new uniforms for the Women’s Voluntary Services (Goodyear, 2003.) with all this in mind. The image below entitled Fig.3 shows examples of said uniforms.

Utility Design & Designers

After all, the war didn’t mean the end of fashion. I would go so far as to say that designers actually reflected social changes. With continued struggles for fabric in fashion, and using uniforms as inspirations, designers for civilian clothing collaborated to produced joint collections. They displayed these collections in exhibitions to convince the public that this functionality can be attractive too.

‘Hardy Amies, Norman Hartnell, Edward Molyneux, Digby Morton, Victor Stiebel and Bianca Mosca were all commissioned to design utility ranges. They produced a practical, durable wardrobe of a coat, dress, suit and shirt or blouse.’ (Goodyear, 2003).

(Fig. 3)

Designers, like the ones mentioned above, saw gaps in the market and took the opportunities to design things that had never been seen, or needed, before. For example, when civilians were encouraged to carry their gas masks with them- as a result of potential gas warfare- designers realized that objects, clothing and accessories’ functions were just as important as their form.

(Fig. 4)

And so, a hybrid handbag-gasmask was born. A clear difference from the cardboard boxes attached to a string that were slung across shoulders, the new stylish bag was a more than perfect blend between both form and function, fit for purpose.

Clothing fashion & body fashion

It seems that the feminine image has always been in focus, however, with the need for uniforms and a utilitarian approach to clothing, at the end of the war femininity was even more emphasized.

It was a common thought that women should be ‘de-masculinized’ and it became clear that society’s message to women was to become, once again, the home-maker. In contrast to women’s roles in the war is equally as difficult as the men’s, now was a time seen to forget about your job and be there to support your man. To make them feel safe and comfortable again.

Wardrobes changed with attitudes. Women were expected to step out of their overalls and step back into their former roles of pleasing men and taking care of family matters and the home in their dresses and aprons. WW2 utilitarian fashion changes had an effect on society’s view of women and their body shapes, let alone their own views on such matters.

Utility morphed into Dior’s New Look, a movement full of an abundance of material, pleats and luxurious materials. This sort of style succumbs to the previous definitions of feminine roles: princesses, brides and debutantes. Vogue explained that this style reveals the ‘real’ woman underneath the previous masculine silhouette brought by uniforms. ‘tight little waists… rounded, almost Rubens-rounded hips.’ (Vogue, 1946).

(Fig.5)

(Fig.5)

Sculptural qualities of the dress came to the forefront: built-in underwiring, corsets and boning limited and constricted waists, padded hips and enlarged breasts. Vogue described these supports as:

‘veins of tiny wires and delicate bones… a wholly new way to let a woman look like a woman’ (Vogue, 1946).

Suggesting that if a woman doesn’t have these idealized assets she cannot be seriously considered as a real woman, and what she dresses in must become part of her being- to work as part of her body. The New Look did not fit all body types and was difficult to reproduce for people who had less money. This brittle, frail portrayal of women quickly became the fashion in the ‘50s, post-war.

Conclusion

A constant battle of what is considered feminine and unfeminine has shaped the fashion industry, specifically, women’s fashion. We have seen that, even in times of war and austerity, women were expected to conform to domestic ideals. I would argue that the women in the M.O.D were less worried about their uniform or clothing choices and more worried about the World War they were in the middle of. This is not to say that discussing their fashions is unimportant…

Durable uniforms served as a reminder that women can partake in tasks that were considered ‘masculine’, and their roles can be just as- if not more- important than their male collogues.

Researching what women wore in wartime has been an enlightening process. I have discovered that wartime women are: adaptable, practical, perceptive, confident and more than able to accomplish tasks, whether that be in war or post-war.

In terms of fashion, the utility scheme put in place in the Second World War resulted in minimal commodities and so when the war was over, society wanted ornate luxury- ruffles and rich fabrics were back.

The result ornate dress styles after the war had on women’s body image was mostly negative in the way that it was barely achievable by the average woman. A woman’s social class was made more obvious by what she wore postwar- the more luxurious, the richer. It can be said that societal pressures pushed the idea of intensified femininity in clothes to compensate for- what they believed-, particularly masculine wartime uniforms. This idea would adhere to patriarchal expectations for women to be invisible and satisfy the male gaze.

Saying this, I would argue, women’s body image was put into focus in a way that it never has been before. Women were empowered knowing they exceeded in serving their country during wartime and so, were liberated in a way they had never previously had experienced. I believe women were more aware of their body types and therefore begin to challenge their place within society. This is why, I believe, fashion during and after the Second World War has impacted society today.

Bibliography

- Campbell, D. (1987). Women in Uniform: The World War II Experiment. Military Affairs, 51(3), p.137.

- Goodyear, J. (2003). Fashions during Wartime. Untitled. [online] Available at: https://www.johndclare.net/wwii13_fashion.html [Accessed 11 Dec. 2018].

- Howell, G. (2012). The Utility Clothing Scheme. Wartime Fashion, 1.

- Mason, A. and Clouting, L. (2018). HOW CLOTHES RATIONING AFFECTED FASHION IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR. Imperial War Museum. [online] Available at: https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/how-clothes-rationing-affected-fashion-in-the-second-world-war [Accessed 11 Dec. 2018].

- McNeil, P. (1993). ‘Put Your Best Face Forward’: The Impact of the Second World War on British Dress. Journal of Design History, 6(4), pp.283-299.

- Rothstein, N. (1984). Four hundred years of fashion. [Place of publication not identified]: Victoria & Albert Museum, p.70.

- Tynan, J. (2011). Military Dress and Men’s Outdoor Leisurewear: Burberry’s Trench Coat in First World War Britain. Journal of Design History, 24(2), pp.139-156.

- Unknown. (1946). Paris Revels in Femininity. Vogue, p.39.

- W. Hill, R. (2005). Rationing and Shortages. BBC- WW2 People’s War. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/84/a4537884.shtml [Accessed 10 Dec. 2018].

- Welters, L. and Lillethun, A. (n.d.). The History of Dress and Fashion. Bibliographical Guides.

- Whiteley, N. (1985). Pop, Consumerism, and the Design Shift. Design Issues, 2(2), p.31.

- Wilson, S. (2018). Rationing in World War Two. [online] Historic UK. Available at: https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Rationing-in-World-War-Two/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2018].

Image References

Figure. 1-

Coupon booklet with instructions on how to use.

Am Baile. (2019). [online] Available at: http://www.ambaile.org.uk/detail/en/8358/1/EN8358-clothing-book-1947-48.htm [Accessed 10 Dec. 2018].

Figure. 2-

Cover of Stichcraft Knitting Pattern Booket, 1940’s

Pinterest. (n.d.). Wartime 1940s Stitchcraft Knitting Pattern Booklet GLOVES STOCKINGS & SOCKS. [online] Available at: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/156359418285822504/?lp=true [Accessed 10 Dec. 2018].

Figure. 3-

Varied uniforms worn by a selection of serving women.

A.Kruse, C. (2017). Stunning Photos of Women’s Uniforms from World War II. [online] Ripley’s Believe It or Not!. Available at: https://www.ripleys.com/weird-news/womens-uniforms/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2018].

Figure. 4-

Respirator (Civilian)/Handbag Combination

Imperial War Museums. (2018). Respirator (civilian)/Handbag combination. [online] Available at: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30016115 [Accessed 11 Dec. 2018].

Figure. 5-

Black silk taffeta evening gown displayed at an exhibition entitled Dior: The New Look at Chicago History Museum, displayed from September 30th 2006- May 27th 2007.

c.1948 Gift of Mrs Sanger P. Robinson. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum.

Supporting Documentation

Initially, I started doing research on Jewelry Design and its progression throughout the ages whilst looking at nature’s influence on its designs. About midway through my research, I realised that there was not as much academic material on the subject as I had hoped and I struggled to find any peer-reviewed or academic writing. I, therefore, made the decision to make my report less specific and narrowed down my research to topics like Fashion Sustainability and Green Design, Utilitarian Design Scheme, The Aesthetics of Kitsch Design, as well as The Challenge of Pop.

I wanted to properly home in on the subjects I found the most interesting so looked at other subjects like Film and searched for journals with ‘Film’ as a keyword. The results were fairly limited but not impossible to work with and seeing as though I had a genuine interest for the subject, I continued to look into the subject further and choose three main journals to start writing this journal with. After this, I decided to focus into Modernism and Post-Modernism in Film. This subject gave me a little to go off, the journal articles I found on this subject provided basic information and I found myself less interested as I delved further into research.

I was having trouble deciding on a topic that both interests me, as well as having credible material to quote throughout my journal. Realizing that I was not totally passionate about the subject of Film, I made the executive decision to go back to topics on the Utilitarian Design Scheme as I had already found enough peer-reviewed journals on this subject and had an interest. I based my article on Peter McNeil’s article Put Your Best Face Forward: The Impact of the Second World War on British Dress. I found this particular article in the Journal of Design History through the JSTOR website. I particularly took inspiration from the layout of the article, with two columns and snappy subtitles throughout.

Saying this, all peer-reviewed articles and journals I read gave me inspiration in one way or another. Many began with an abstract or introduction outlining what the article included and set its main goals and themes. I decided this technique would be suitable with my journal as it would help me whilst writing, having something to refer back to, making sure main arguments are covered and actually make sense. As other journals I had looked at had done, I included subtitles to keep the journal interesting and easy to follow, with separate subjects in separate paragraphs. A lot of articles I read included a keywords list, I thought this was interesting and found that the journals with Keywords were more interactive. This is why I included Keywords and Key Names in my journal, as well as providing an easily accessible point to go off for possible furthered research.

The inclusion of images was imperative to illustrate certain things that may be difficult to imagine. Along the way, I found it surprising to physically see the dramatic change in clothing and the effect the fashions had on the impressions of an ‘ideal’ body of the times. Writing about what women are expected of is a passionate subject of mine, especially in current climates, but shedding a light on what fashion’s part has played on this has been an eye-opener.

The industry really does pray, feed and make money off human insecurities, especially women’s. Whilst historic art has exhibited the fascination and exploitation towards women- more specifically, their bodies- it is fascinating to notice the change that WW2 utilitarian fashion had on society’s view of women and their body shapes, let alone their own views on such matters. I found it more interesting to research the feminist issues associated with clothing rather than the actual fashion of WW2. For this reason, if I were to write an article like this again, I would prefer to focus in more on this subject and to write more critically. I believe it would be more interesting to look at the Second World War as a separate matter to Fashion and to look into both with detail.

That being said, I feel my article discussing the WW2 Utility Scheme and its Impact on British clothing, body image, and society, suits the aims of the peer-reviewed journal Put Your Best Face Forward: The Impact of the Second World War on British Dress and have achieved inspiration for various aspect of said article successfully, referencing it in my own.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal