Effectiveness of Feminism in Fashion

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Fashion |

| ✅ Wordcount: 4011 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

An analysis of how effective Fashion and Feminism is in appealing to learners and/or audiences, including recommendations on how to extend this appeal.

Figure 1. Fashion and Feminism exhibition Ulster Museum (photograph: N.Cavanagh December, 2018)

Figure 2. Fashion and Feminism exhibition Ulster Museum (photograph: N.Cavanagh December 2018)

When one enters the exhibition Fashion and Feminism it overwhelms; the space is adorned with fabulous creations from dresses to hats to sunglasses. It traces the links between fashion and feminism from the 1800s to the present day with a focus on celebrated designers and accomplished women. It seeks to provide visitors with ‘the opportunity ‘to explore the correlation between self-expression and fashion’. (Irish News/BBc)It is a timely exhibition with the prominence of women’s issues reflected in the MeToo campaign; repeal the 8th and the centenary of women’s suffrage. For any effective learning processes to take place the visitor needs to be entertained engaged and inspired by what they find, if we judge the exhibition by this criteria on the whole it has been a success. However in our understanding of learning it is critical that we understand the personalised and contextualised nature of learning and that learning takes place over time. (Rennie and Johnston; 2004) These factors are critical in assessing the impact of the exhibition and its appeal. We are told upon entering the exhibition ‘that fashion touches all our lives’. If we are to consider how effective this exhibition is then we must also consider the museum as a communicator of this message and too whom it is communicating (Hooper- Greenhill; 1994 a, 2000). We much also acknowledge the active process of meaning making on the part of the learner. (Hein; 1998) Hooper speaks of a ‘post –modern museum visitor’. This is a visitor who is actively engaged but should not only be explained by learning theories alone, but communication, literary and cultural theory. (Hooper- Greenhill (b) p.67)It is with this in mind that this exhibition will be interrogated using a number of theories from educational, communication, cultural and literary theory.

This exhibition will be assessed against the Generic Learning Outcomes (GLOs) proposed by the Inspiration for Learning Initiative. These outcomes include an increase in knowledge and understanding, the acquisition of new skills, a change in attitudes and enjoyment, inspiration and creativity. The final skill action, behaviour and progression relates to what people intend to do and their future actions. This would require an in-depth evaluation that is impossible at this time. It will also take into consideration John Falks and Lynn Dierking’s(2000) Contextual Learning Model (CLM). At the centre of this model is the notion that learners engage in free-choice learning. Learners have control over what and when they learn. Additionally it stresses visitor learning should be assessed under three interconnecting and overlapping contexts; the physical, personal and socio-cultural. For the purposes of brevity this essay will focus on the personal and socio-cultural contexts. The personal context focuses on motivation, expectations, beliefs and prior knowledge and experience of the visitor. The socio-cultural includes in group and facilitated mediation. Furthermore a constructivist learning theory will be applied with its emphasis on active learning, participation and construction of knowledge. (Hein;1998). A cultural communication theory with its emphasis on interpretative communities will also complement this approach. (Hooper- Greenhill; 1995) A process of dialogic looking will also be broached as this will provide an alternative to facilitated learning experiences in the museum and encourages the development of interpretative strategies within the art museum. (McKay and Monteverde; 2003).

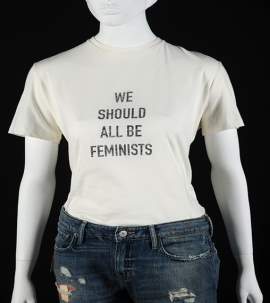

Fashion and Feminism as an exhibition can be seen to have adopted a strongly constructivist approach. In essence this exhibition can be seen to allow the visitor to draw their own conclusions based upon their own personal knowledge. Discussion is linked to concrete examples and contemporary trends. It also allows the visitor to make connections between familiar concepts and objects. It is in this way that the visitor is able to make meaning-making with what they already know. Again this is a key principle of the constructivist museum. (Hein 1998). For instance two key pieces, a Missoni ‘Pussy Hat’ (2017) (Figure 3), based on the worldwide ‘Women’s March’ of January 2017, and the iconic ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ T-shirt designed by Dior (2017) (Figure 4), inspired by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s essay and TEDx talk of the same name, can encourage and motivate the viewer to seek out and find new answers. It is in this endeavour that opinions and attitudes may be revised. It may also spur the viewer into making their own ‘confident feminist statements’. All of these are GLOs. A key element of constructivist theory is the need for the building upon and the further development of the existing knowledge of the learner. (Hooper –Greenhill (b);1994) In this instance the exhibition has provided provision for this.

Figure 3. Missoni ‘Pussy Hat’ (2017) Figure 4. ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ T-shirt

Fashion and Feminism, Ulster Museum. Dior (2017) Fashion and Feminism, Ulster Museum.

(photographs: N.Cavanagh December 2018)

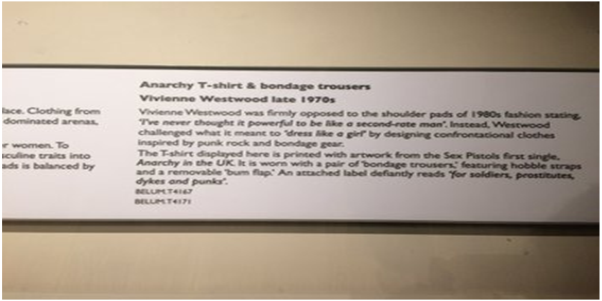

This exhibition for the most part has adopted a cultural approach to communication following strongly along a constructivist approach to learning. This is in stark contrast to the transmission communication model that adheres to the behaviourist approach to learning. This form of communication stresses the need for interpretative strategies in the process of meaning-making. (Hooper-Greenhill ; 2000) The process of learning within this exhibition is both circular and dialogic. Although the significance of these garments is pointed out to us, it is always cross –referenced with contemporary concerns and relatable to personal contexts, which encourages some to ask questions. (Hooper –Greenhill (d); 1994)Within the constructivist approach the labels should encourage us to ask not only ask questions of the objects but of ourselves. (Hein; 1998, 1994) For instance the label below is particularly provocative the designer Vivienne Westwood asks us to question what it means to ‘dress like a girl?’ and the even more explosive statement ‘I’ve never thought it powerful to be like a second rate man.’ However these labels can only be fully effective if the visitor has the adequate tools and interpretative strategies at their disposal for a probing reflective analysis.

Figure 5. Label accompanying Vivienne Westwood garments, Fashion and Feminism Ulster Museum. (photograph N.Cavanagh December 2018)

Learning opportunities should simultaneously encourage social interaction and contemplation. Thus a key goal of the exhibition should be to support sociability; not only is this a key generic learning outcome but also central to the CLM. The socio-cultural context of this model encourages visitor group mediation and can encourage facilitated mediation on the part of a more knowledgeable person. This creates a nourishing environment for collaborative learning to occur (Chang; 2006 pp.179-180). In the context of this exhibition the labels do provoke questions and debate. However the introduction of a docent or member of staff can help ‘scaffold’ the learning process, as Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development promotes (Wood, Bruner and Ross; 1976).All learning is a social experience and museums must help facilitate this. Thus, it is important that motivated visitors can share and collaborate with a docent, on their own initiative, in a relaxed and comfortable atmosphere. Hooper-Greenhill in her analysis of visitor’s interpretations in an art museum has found that visitors look for additional help, which is usually absent in the museum setting and frequently struggle to employ adequate interpretative strategies in the art museum. (Hooper-Greenhill ; 1996)

This social dimension to learning may also be extended by the dialogic looking approach. Although this approach has been applied to traditional art it was felt that it could be successfully extended to this exhibition. It is a three-fold approach to meaning – making whereby a dialogue takes place internally, within a group and with the artwork itself. (McKay and Monteverde 2003)This dialogic looking creates Baktin’s herteroglossia, where multiple voices arise causing new ideas both agreement and dissension (Mayer; 2005). Moreover this dialogue creates a situation where the viewer is both affecting and being affected by the artwork. Dialogic looking should be an organic process that can arise naturally within a group setting. For effective dialogic looking to occur however the museum should also encourage the process. (McKay and Monteverde 2003) For example before entering the exhibition there is a short synopsis about the exhibition which encourages us to question the concept of gender and that feminism is both ‘politically engaged and challenging’. These questions can only be fully appreciated when supplemented by the labels. The labels that accompany most of the objects are at floor level and poorly lit thus crouching down to look at over thirty labels is very difficult. Indeed straining to look at these labels diminishes the magnitude of the garments on display. Perhaps a small brochure or leaflet could also be provided which draws attention to these ensuing dialogues, such as the differences in the designs and shapes of the dresses. How have the designs of the dresses evolved? How do these physical changes reflect contemporary concerns? Conclusions can be drawn by just an observation of the clothes. This also forwards the free-choice learning approach.

Moreover something as undemanding as a comments board or an area where visitors write their own labels should also be considered. This may facilitate further group dialogue and the expectation of group participation. There is little active encouragement on the part of the curator to engage the visitor to view the dress as part of the whole. The space is created for these dialogues to occur, but without added support this possibility is minimized. It should not be assumed that these dialogues are axiomatic and will just happen. These dialogues also help stimulate the learning process. Dialogic looking engenders an inquiring mind within the visitor and furnishes the visitor with the tools necessary to view other works of art in a penetrating and engaged way in the future, thus complementing the life-long learning approach. A fundamental GLO and central to the CLM.

Although there are many constructivist elements within this exhibition there also appears to be some didactic components. For example the exhibition follows a clear linear sequential order. Crucially there is not a diverse range of entry points or a wide range of active learning modalities, which is central to the constructivist approach. (Hein; 1994)The addition of interactives such as sound or video projections could help with this. A key highlight is a pair of black slippers (Figure 6) on loan from London-based designers Teatum Jones’ current AW18 collection which has the theme of ‘Global Womanhood’. As part of their campaign they released a video that is widely available which questions what it is to be a woman. It includes a number of women from a variety of backgrounds with sound bites of their experiences. The slippers when taken in isolation are just that a pair of plain black slippers. The juxtaposition of the plain slippers with the personal vignettes encourages not only a new affective appreciation of the slippers but a greater introspection on the part of the visitor of what it means to not only be a woman, but also a feminist. This is a key objective of the exhibition.

Figure 6. A pair of black sippers, Teatum Jones AW18 collection, Fashion and Feminism, Ulster Museum (photograph N. Cavanagh December 2018)

Figure 6. A pair of black sippers, Teatum Jones AW18 collection, Fashion and Feminism, Ulster Museum (photograph N. Cavanagh December 2018)

Interactive experiences help facilitate an added opportunity for further layers of learning and deeper experiences. (Hooper-Greenhill;1991) Thus this would provide further assistance for the visual auditory leaner. These devices can also have an active and important role to play in the communication process. For instance they could also be utilised to show how the garments were made. We may also view the garments on living bodies on the catwalk or in day to day life. This can facilitate an additional affective dimension to the garments. Archival films of fashion shows or women in action (such as protest or making the garments) could be projected onto the background of the dresses. Moreover if a digital database accompanied the exhibits we would be able to undergo a larger contextual analysis of the designers and a comparison of dresses through the prisms of time, function and class. Perhaps this database could go even further and provide a forensic analysis of the garment before during and after the conservation process complete with the cost and time that it took. This will enable a greater understanding of the life cycle of the garment. It is clear from the research that visitors find interactives more entertaining. (Witcomb;2006) It is hoped that the introduction of interactives in this exhibition, would offer a further exploration of ‘the social context, subject matter and emotional content …the materials and tools of the artist’. (Simpson; 2002 8)

In addition the employment of photographs and sketches of the dresses will help move the visitor beyond that of a mere shopping excursion towards a greater engagement and intimate understanding of the garments. It also provides a further entry point for the visual leaner. We can also view the designer’s initial concept. Moreover, photographs and sketches offer the opportunity for the dresses to be observed from the back. This is a major drawback with this exhibition. (Palmer;2008) It is imperative that we are provided with a three- dimensional view of the garments on display. These garments can elicit emotional responses, memories and feelings; thus additional resources can facilitate a more prolonged active, engaged and hopefully embodied experience. Michael Spock has referred to objects that make an indelible impression as ‘landmark learning’ (Gurian Heumann; 1991 p. 181). However the presence of these supplementary resources perhaps in a catalogue or on labels could work in conjunction with this to create an aha phenomenon when the viewed items, upon later reflection, are understood in a more satisfying and profound way. This approach conforms to both the constructivist and CLM. It supports future reflection and encourages the visitor to integrate the museum experience into life after the museum visit. Taking these proposals into consideration it is clear that they may act as a substitute for the absence of touch (Palmer;2008).

A key GLO is the acquisition of new skills. (I.F.L) Furthermore crucial to the constructivist approach and the CLM is the need for hands on experimental learning. In this area this exhibition can be found to be greatly lacking. In the 2002 V&A Gianni Versace exhibition a small study room was incorporated beside the exhibition. The visitors were encouraged to touch and examine the garments on display. This advanced the meaning-making process (Steele; 2008). Whilst handling may be impossible for the earlier garments in the Fashion and Feminism exhibit, with the later garments this should not only be a possibility but an assurance. Replica materials can be employed quite easily and cheaply. Although activities and events are already in place to complement the exhibition; thus far there have been two academic lectures. Additional workshops within Discover Art could also help visitors learn and develop new skills such as sewing or even creating their own garments. For effective experimental learning to take place the visitor should be encouraged to engage in ‘reflective observation’ of their visit. They should also be encouraged to situate this reflection and their experience in their day to day life (Moon;1991 101). These workshops could help facilitate a greater understanding of how these garments were mass –produced and how this occurs today in the clothes that they wear. Visitors should be encouraged to produce an emotional overlay onto the objects only then will meaning be produced. Furthermore museums should not shy away from employment of these emotional strategies.

The Way We Wore displaying clothes and jewellery from the 1760s to the 1960s successfully weaves interactives, pictures and sketches into a progressive multisensory experience.

Figure 7. The Way We Wore, National Museum of Ireland (photograph N.Cavanagh June 2018)

With regards to this exhibition it is important to note the presence of ‘interpretative communities’. This is a useful concept for understanding the experience of the visitor at this exhibition. All learning is culturally inflected and is refracted through social dimensions. It is through these communities that our knowledge is negotiated and communicated and our shared experience expressed. Thus the process of any individual meaning making is analysed in the context of this community. (Hooper-Greenhill: 1994 (c), 1995, 2000) It is clear that this exhibition is geared very much towards white educated women and its direction is to appeal to this community. Additionally the exhibition requires a degree of cultural capital such as special knowledge to interpret or decode many of the displays (Bourdieu: 1984 pp. 2-3). For instance there are four large portraits each of noteworthy women. The labels that accompany these portraits are so small that they are barely legible. The lay person would struggle to know who these women are and their importance to the exhibition in general. The interpretative strategies necessary to read such art may also be absent. There are also a number of quotes by prominent feminists and designers; however without an exhaustive examination of the exhibition, or prior knowledge, they can give the impression of frivolity and superficiality (See above Figures 1 and 2).

As with the CLM prior experiences and knowledge leads to differentiated meanings and complexities of interpretation (Falk and Deirking; 2000). It is this cultural background which plays an important role in attributing significance. Through active interpretations of our experience then knowledge is constructed. As socio-cultural background is paramount it is imperative that the exhibition is multi-vocal and offers more than a one-dimensional approach (Chang;2006). This exhibition offers a very traditional feminist approach, albeit informed with a contemporary focus. As these garments are reflective of the struggle and progression of feminism, it would appear that they are reflective of a certain kind of feminism. The garments on display and the designers that are showcased are geared predominately towards the white middle class educated woman. Every woman that is featured in the exhibition was a renowned upper or middle class white woman. These noteworthy women are used to illustrate contemporary trends. For instance the works of Virginia Wolf and Mary Wollstonecraft are at times tenuously applied as inspiration for contemporary designers. A casual ‘comfortable and sexy suit’ is put on display as its former owner was Lauren Bacall who was a ‘Hollywood legend’ and perhaps more questionably ‘the embodiment of self-assured womenhood’. The focus on this ‘famous’ demographic only serves to isolate certain audience members. It may have been possible to incorporate dress from other cultures and rather than focusing on Feminism as an all encompassing universal theory focus on the intersectionality of Feminism or even Feminsims. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s essay and TEDx talk both reflect this approach to Feminism. It is strange that given the prominence and saliency of Adichie’s essay that it is regulated to a single quote in the exhibition. In From Knowledge to Narrative (1997)Lisa Roberts stresses that museums impart the ‘official’ narrative, it is visitors who create their own narratives, ostensibly then, it is the visitor rather than the curator who creates the narrative. However in this case many visitors who do not find their needs reflected in the objects on display may just turn off and leave. McReyonlds states, ‘fashion has managed to make statements of how women want to be represented’. (Irish News) This statement should be extended to this exhibition for the selection of certain dress and the elision of others highlights the dynamics of power within the museum and suggests if even on a subconscious level this is how the museum feels women should be best represented.

In conclusion, Fashion and Feminism is a must see exhibition for any self-respecting fashionista but its appeal stretches far beyond the aesthetic. It provides a strong educational and entertaining platform for those interested in feminism as reflected through the medium of fashion. Thus it fulfils a number of the GLOs, CLM and constructivist principles. However this appeal can be extended, the exhibition does not reflect the diverse learning styles of visitors or the diversity of its audiences. It must construct as many entry points and be as multisensory an exhibition as it can to cater for as many learning styles without prejudice as possible. It must also enable both the use of visitors’ prior knowledge and the development of new knowledge. It is hoped with the addition of interactives that this can be achieved. In encouraging both facilitated and non-facilitated dialogue it is hoped that this will impart the visitor with a greater capacity for deductive thinking and greater accessibility when viewing further works of art. There should also be a range of hands on activities; it is only by active participation that learning in the exhibition can be viewed to be a success for the viewer. Furthermore, museums should also try and appeal to as diverse an audience as possible, with the presentation of a range of viewpoints. It is felt in this area that this exhibition is lacking. Fashion is an iconography to express not only an individual but a collective identity. In this case it is quite homogenous in its representation of women. Authentic representations of all women are imperative not just those women exhibited in the language of the exceptional. Thus diversity should not only be reflected in the garments showcased but by encouraging multiple dialogues on the part of the curator and the visitor. It is the socio-cultural analysis which is more pronounced in this evaluation than the constructivist. It is hoped with these recommendations in place that this exhibition will leave a lasting and profound cognitive, social, aesthetic and kinesaethic experience for all its visitors.

Bibliography

- Bourdieu Pierre, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1984)

- Chang EunJung, ‘Interactive Experiences and Contextual Learning in the Museums’, Studies in Art Education 74, (2) (2006), pp.170-186.

- Falk John and Dierking Lynn, Learning from museums: Visitor experiences and the making of meaning (Walnut Creek: AltraMira Press 2000)

- Gurian Huemann Elaine, ‘Noodling Around with Exhibition Opportunities’, in Karp Ivan and Lavine D. Steven, Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press 1991), pp 176-191.

- Hein George, Learning in the Museum (London: Routledge 1998)

- Hein George, ‘The constructivist museum’, in Hooper – Greenhill Eilean, The Educational Role of the Museum, (London: Routledge 1994), pp.73-80.

- Hooper – Greenhill Eilean, Museum and Gallery Education, (London: Continuum 1991)

- Hooper – Greenhill Eilean (a), ‘Communication in theory and practice’, in Hooper – Greenhill Eilean, The Educational Role of the Museum, (London: Routledge 1994) pp.28-44

- Hooper – Greenhill Eilean (b), ‘Museum learners as active postmodernists: contextualising constructivism’ in Hooper – Greenhill Eilean, The Educational Role of the Museum, (London: Routledge 1994) pp.67 -73.

- Hooper – Greenhill Eilean (c), ‘Education, communication and interpretation: towards a critical pedagogy in museums’, in Hooper – Greenhill Eilean, The Educational Role of the Museum, (London: Routledge 1994) pp3 3-28

- Hooper – Greenhill Eilean (d), ‘Learning in art museums: strategies of interpretation’ in Greenhill Eilean, The Educational Role of the Museum, (London: Routledge 1994) pp.44-53.

- Hooper – Greenhill Eilean, Museum, media, message, (London; Routledge 1995)

- Hooper – Greenhill Eilean, Improving museum learning, (Nottingham: East Midlands Museums Service 1996)

- Hooper – Greenhill Eilean , ‘Changing Values in the Art Museum: rethinking communication and learning’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 6. (1) (2000), pp.9-31

- Mackay Sara and Monteverde Susana, ‘Dialogic looking: Beyond the mediated experience’, Art Education, 56 (1) (2003), pp.40-45

- Mayer Melinda, ‘Bridging the Theory – Practice Divide in Contemporary Art Museum Education’, Art Education, 58 (2), pp.13-17.

- Moon Jennifer, Reflections in Learning and Professional Development (London: Kogan 1999)

- Palmer Alexandra, ‘Untouchable: Creating Desire and Knowledge in Museum Costume and Textile Exhibition’, Fashion Theory 12 (1) (2008), pp 31-63.

- Rennie Leonie and Johnston David, ‘The nature of learning and its implication for research on learning from museums’, Science Education, 8, 51 (2004), pp 4-16.

- Roberts C. Lisa, From Knowledge to Narrative: Educators and the Changing Museum, (Washington: Simthsonian Institution Press 1997)

- Steele Valerie, ‘Museum Quality: The Rise of the Fashion Exhibition’, Fashion Theory 12 (1) 2008 , pp7-30

- Wood David, Bruner Jerome, Ross Gail, ‘The role of tutoring in problem solving’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17 (2), pp.89-100.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal