How Is It Possible to Study People, Rather than ‘Art’ or ‘Architecture’ or ‘Objects’, Through Material Remains?

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Archaeology |

| ✅ Wordcount: 1931 words | ✅ Published: 03 Nov 2020 |

The expression of civic identity can be interpreted through material remains such as funerary monuments during the Roman period, as they provide material testimony of one’s life as well as facilitating status, recognition, legitimacy and identity amongst the living.[1] The reason for these beliefs is extensive due to being principally connected with a desire for status and recognition within the community as well as a fear of annihilation, which leads for a desire to be immortalised.[2] This was important in commemoration leading to many individuals seeking immortality in the world of the living by erecting monuments that celebrated their lives and allowed fragments of their existence to remain.[3]

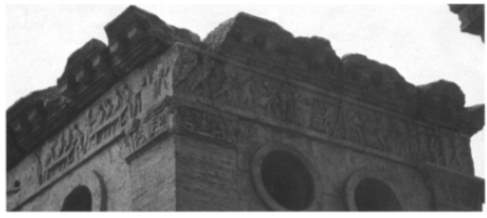

It has been demonstrated religious beliefs were unaffected by economic status which meant individuals from the lower class would have been equally afraid of their existence being forgotten. Unlike wealthier members of the community who were often honoured with statues in the Forum and commemorated themselves by virtue of their public works and generous gifts to the community, the lower classes lacked significant opportunities to publicly memorialise themselves during their lifetime.[4] Thus, the commemorative properties of funerary monuments and activities assumed particular importance.[5] This is evident in Rome’s complex past of non-elites (libetini) who had complex lives, from having been slaves freed by their masters to become Roman citizens. [6]During the Augustan period, a baker named Eurysaces built a giant grain silo and ovens whilst bearing a frieze depicting himself at work. [7]The tomb makes it apparent not only about his economic success, but rather how this was achieved. It is presumed Eurysaces had a ‘freedman’ identity, his motivation is speculated through the commission of the tomb and the ostentatious display of the baker’s financial success which is shown through the unconventional use of architectural form as well as decoration.[8] The notable décor of the tomb is sculpted pictorial friezes elaborating in visual terms while the epitaphs below convey into words. Depicting various stages of bread making in a large-scale commercial setting; the intriguing circular forms in the third or upper story; and, below the cornice, a sculpted pictorial frieze that depicts various stages of bread making in a large scale commercial setting, such as ‘’the consignment and grinding of grain (south), mechanical kneading of dough, formation of dough into loaves, bread baking (north), and weighing of bread.’’[9] Therefore, unified in concept; this is a tomb of a baker and baking contractor, who owned a huge establishment, emphasised that it was the same size as the tomb itself.[10] In addition, scholars have noted that a marble relief portrait of Eurysaces and his wife Astia were found nearby, it has been suggested that this belonged to the eastern façade due to the scale and uniformity. [11]

Figure 1: Model of the monument of Eurysaces.

Figure 2: South Frieze.

Figure 3: North Frieze.

Figure 4: West frieze.

Figure 5: Marble portrait of Eurysaces and Astia.

The visual strategies did not differ significantly from the ones used by prominent Roman citizens at the time.[12] It could be noted through the unconventional form of the monument to the portraits of the individuals. Kleiner argues the style of ‘freedman’ portraits imitate the aristocratic attire, with Eurysaces wearing that of the traditional veristic style of the Republic. While Astia displays coiffures similar to the contemporary style worn by aristocratic women.[13] Kleiner believes the portrait of Atistia and her husband fits well into this trickle-down model, in which the aristocracy establishes stylistic trends that the lower strata imitate.[14] Although, not all familial funerary portraits designate the social standing as depicted, but in the epitaphs of Eurysaces’ and Atistia’s epitaphs, there is no formal legal status that appears with their names.[15] It was common for a freed slave to use the abbreviation ‘L’ but not universal, this was notably absent from the inscriptions but due to the medium and style used, it has been asserted that the husband and wife were ‘ipso facto’ ex-slaves.[16] Referring back to the name Eurysaces, it was considered a Greek rather than a Latin name, has led some to conclude that he had been a slave of Greek origin.[17] It was known that labour-intensive activities of baking were typically associated with slaves, but nonelite citizens, which included freed slaves, could own bakeries in addition to working within them. This could link to the unconventional appearance of the monument, being specifically associated with the association of Eurysaces identity being that of a wealthy ex-slave.[18] As well as the location of the monument, where Eurysaces had to contend against his neighbours for perpetuation of memory. Near his tomb was another complexed monument of that of an elite whom worked with Augustus, which is now known Porta Maggiore, which included his descendants and hundreds of slaves. Thus, suggesting that Eurysaces tomb participated in dialogue with its neighbours – freed slaves and born elite alike. [19]

Figure 6: Map surrounding the area of Eurysaces.

Like that of Eurysaces funerary monument, the gravestone of Regina bears a striking resemblance to circumstances of her past being a slave. The Aramaic inscription highlights the strong link between ethnic identity language also clear in Palmyra itself where Aramaic in commemorative inscriptions was never replaced by Latin or Greek. Though her biography was mainly written in Latin.[20] The desire of the Palmyrene community in general to preserve its cultural and‘ the insignia of women’ religious identity in a foreign environment has been demonstrated elsewhere, for example at Dura Europos on the Euphrates.[21] Scholars note that form of dress in general can function as a form of code through which people communicate to their audience their place in society, or identity, this was reinforced by Regina’s non-Roman attire in the portrait. This possibly reflects her attire in life or the idealised version of dress, signifying status and ethnic belonging.[22] It could be suggested that Regina herself may have requested her husband to be depicted in this manner, as she wanted to visibly notify her peers of her status, as well as wealth, power and ethnic affiliation. Her dress and bodily adornment were instrumental in making a social persona from which ethnic affiliation, wealth and status could be read. But her social persona also entailed gendered behaviour and the manifestation of feminine virtue.[23] With visible evidence of her skills in spinning and wool-working, Regina appears as an ideal wife, an image that resonated in Roman society in Italy as much as in the western and eastern provinces of the Roman world. The desire for women to appear as legitimate and diligent wives must have been particularly strong in communities like Arbeia where there were real constraints on valid Roman marriage and where women often had limited legal or even social rights.[24] In context, the presentation of Regina conveys her as being a respectful, modestly clothed wife, constructing ideals in both death and perpetuity.

Figure 7: Gravestone of Regina.

Figure 8: Wool working equipment.

Referring to the latter, both funerary monuments depict both individuals bearing similar realities of their past with their present identities being overlapped. This is particularly evident in the disparity between status and gender, where both monuments and inscriptions have given a closer insight to that of the Roman world and the ideals that came along with it. It is apparent both individuals do not conceal their ethnic identity nor of their past, but rather acknowledge it and mention accomplishments in their life. Although, it could be suggested that idealised roles for both the deceased may have been created at death, due to the competitive display and elaboration of a temporal nature with restraint replacing extravagance as an indicator of status.[25] This could be linked to both monuments, as for Eurysaces, he glorified his monument by stating his bakery was of large proportions. But excavations near his site contradict his statement and indicate that bakeries tended to be small complex operating on a smaller scale.[26] This was similar to that of the tombstone of Regina, whom was represented as a modest wife, which was the idealised representation of how women should behave. Thus, with both monuments, it is apparent that both individuals wanted to convey these specifications as being integrated into their identities. But through these idealisations, lack reliability in how they were in their life, although, by examining these monuments, it has enabled scholars and archaeologists alike to gain insight into the conventions of Roman society, and how civic identity was portrayed according to certain individuals.

To conclude, it is apparent the theme of civic identity comes of importance when linking to funerary practices in the Roman world, regardless of economic status many strived to be immortalised in memory. This was evident in that of the funerary monuments of Eurysaces and Regina, whom were both ex-slaves, but became on a similar level with the elite. Although, it could be argued that the idealisations of Roman society may have glorified both monuments, allowing both monuments to fulfil the standards that would make them both notably worthy of being remembered. Though the depictions of both identities may have not been reliable, nor factual, it allows scholars to gain insight into the ideals of their desire of recognition, status and identity to be conveyed amongst the living. (Word count: 1625)

Bibliography

- Caroll, Maureen. ‘‘The Insignia of Women’: Dress, Gender and Identity on the Roman Funerary Monument of Regina from Arbeia’, Archaeological Journal 169 (2012), 281-311.

- Carroll, P.M. Ethnicity and Gender in Roman Funerary Commemoration: Case studies from the empire’s frontiers, in: Tarlow, S. and Nilsson Stutz.(eds.) The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial. (Oxford,2013), 559-579.

- Croxford, B. Goodchild, H.Lucas, J., and Ray, N. (eds.) (2006) TRAC 2005: Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Birmingham (Oxford, 2005).

- Heyn, Maura. ‘Gesture and identity in the Funerary Art of Palmyra’, American Journal of Archaeology 114 (2010), 631-661.

- Hope, Valerie. Constructing identity: The Roman funerary monuments of Aquileia, Mainz and Nimes. British Archaeological Reports, International Series 960 (Oxford, 2001),

- Jones, Nathaniel. Exemplarity and Encyclopedism at the Tomb of Eurysaces. Classical Antiquity 37 (2018), 63-107.

- Petersen, Lauren. ‘The Baker, His Tomb, His Wife, and Her Breadbasket: The Monument of Eurysaces in Rome’, The Art Bulletin 85 (2003), 230-257.

- Toynbee, J.M.C. Death and Burial in the Roman World. (London, 1971).

- Verboven, Koenraad and Christian Laes, (eds.) “Work, Labour, and Professions in the Roman World.” Impact of Empire. Boston (2016).

- Yasin, Ann. ‘Funerary Monuments and Collective Identity: From Roman Family to Christian Community’, Art Bulletin 87 (2005), 433-457.

[1] EJ, Graham, 57.

[2] Maureen Caroll, 3.

[3] EJ, Graham, 66.

[4] EJ, Graham, 66.

[5] EJ ,Graham, 67.

[6] EJ, Graham, 66.

[7] EJ, Graham, 66.

[8] Lauren Petersen, 231.

[9] Lauren Petersen, 231.

[10] Lauren Petersen, 231.

[11] Ciancio Rossetto 3-79 cited in: Exemplarity and Encyclopedism at the Tomb of Eurysaces, 64.

[12] Verboven, Koenraad and Christian Laes, (eds.) ‘Work, Labour, and Professions in the Roman World.’ Impact of Empire. (Boston, 2016), 267.

[13] Diana Kleiner, an Group Portraiture: The Funerary Reliefs of the Late Republic and Early Empire (New York,1977) 118-57 cited in: The Baker, His Tomb, His Wife, and Her Breadbasket: The Monument of Eurysaces in Rome,

[14] Diana Kleiner, an Group Portraiture: The Funerary Reliefs of the Late Republic and Early Empire (New York,1977) 118-57 cited in: The Baker, His Tomb, His Wife, and Her Breadbasket: The Monument of Eurysaces in Rome,

[15] Lily Ross Taylor, “Freedmen and Freeborn in the Epitaphs of Imperial Rome,” American Journal of Philology 82 (1961) 113-33, referenced in: Lauren Petersen, Insignia of Women, 237.

[16] Lauren Petersen, 237.

[17] Tenney Frank, “Race Mixture in the Roman Empire,” American Historical Review 21 (1916): 689 cited in Lauren Peterson, 230.

[18] Nathaniel Jones, 65.

[19] Petersen, 241.

[20] Mullen, A. 2011. Latin and other languages: societal and individual bilingualism, in J. Clackson (ed.) A Companion to the Latin Language, 527–48, London: Wiley-Blackwell cited in: Maureen Carol, 285.

[21] (Dirven 1999, 192–95). Cited in Maureen carol, 286.

[22] Maureen Carol, 299.

[23] Maureen Carol, 304

[24] Maureen Carol, 305.

[25] Valerie Hope, 6.

[26] Nathaniel Jones, 91.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal